Aris Kalaizis is a painter. He lives and works in Leipzig where he grew up as a son of Greek immigrants. It was also here where he completed his art education as “Meisterschueler” with Arno Rink. Because of this he is often attributed to the Neue Leipziger Schule. His paintings are realistic and surreal at the same time. They combine dream and reality. The American author and scientist Carol Strickland invented a specific word for it: Sottorealism.

Characteristic of his work is the time-consuming process in which his paintings develop. It includes several stages ranging from achieving a state of inner emptiness and receptiveness, via creating and photographically documenting a scenery (depending on the season inside the workshop or outdoor), where craftsmen, background actors or real actors become part of the scenary to the actual realization of a painting in his studio in Leipzig.

Here, in the loft-like premises of a former printing and publishing house of the early 20th century, Aris Kalaizis welcomed Age of Artists end of July of this year. We talked to him about his background, his work as an artist, the art of living, doubt and crisis, the question of how and what people can learn from art, and about the pursuit of insight and enlightenment:

“Maybe we have to abandon the idea of enlightenment, and that people, when they sit down and deal long enough with enlightenment they become similarly enlightened. On the contrary, we should assume that we are nothing. As people we are nothing. We are not even human. We are the design of a human being. Throughout our lives we have to gradually become humans by our deeds. Good deeds more or less. As such we establish ourselves as humans or gradually develop into a human being. Along with it goes the fact that we are not really rich in wisdom, as Enlightenment suggests, but rich in foolishness. We are full of foolishness and we have to spend this foolishness throughout our lives as if it was useless ballast. Because we gain experience, because we make mistakes, and everything that goes with it. Then, I think, we get a little further in our relationship with individuation, which is for many people of our time a burden. It’s not only a pleasure. An artist, a painter, I say, sees it as a pleasure. But many people see the difficulty of being an individual as a load or or something to be afraid of.”

Read the complete interview with Aris Kalaizis online

Introduction

Aris Kalaizis lives and works in loft-like rooms located in an early 20th century building, once used by the printing industry. Having welcomed us warmly in his apartment, he asks us to wait a few minutes in his adjoining atelier, while he finishes writing an email. We use this time to familiarize ourselves with his working environment. We enter a large room with high ceilings and a row of windows spreading across the entire breath of the room that flood the atelier with light, while keeping people’s views out. The lower section of the windows is coated with film for privacy purposes. The right side of the room houses the actual working area. This is where his easel is set up with a large Persian rug sprawling out in front of it. There is enough space to take a few giant steps backwards, away from any painting. Otherwise empty, a canvas prepared with green primer is propped up on the easel. Before we officially begin our interview, Aris Kalaizis tells us about one of his new projects, a painting concerned with St. Bartholomew. It will be one of the largest paintings he has made thus far. In order for it to leave his atelier, the canvas will need to be taken from its frame. He also doesn’t plan using a model of the scene.

On the left hand side of the room, the artist stores canvas and props behind a free-standing wall covered in Baroque-style wallpaper, decorated with a ram skull that had also served as a prop in a previous painting. A hospitable suite is set up in front of the wall, including a coffee table, a sofa, and two armchairs.

Interview

AoA: We are interested in discovering how and what humans or individuals may learn from art, in order to bring about change in society. Change that, in our view, is urgently needed. The financial crisis, the economic crisis, economic growth at any cost, digitalization, automation, the end of privacy, and many other issues have brought about a feeling that something needs to happen. We believe that one ought to start on the level of individuals and that a large fraction of that, which it will take to cause change, might be found in artistic attitudes and artistic actions.

Aris Kalaizis: Those are certainly important questions and good observations. I actually agree with what you are saying. Aristoteles opens his Nicomachean Ethics with the idea that every human being strives for knowledge or illumination. Today we ought to note that this idea is subject to revision, as human beings, who are actually free to strive for that good, are instead actually striving to avoid greater knowledge. Or the experience that goes along with attaining it. What happened? My guess is that since the dawn of modernity – as nice as modernity maybe – three areas of human dexterity have come to dominate everything else: technology, science, and economics. Among these three areas, there is, of course, plenty of overlap. With other areas beyond those three, just mentioned, there is less overlap. In addition to that, we may observe that the dualities of human inner-life have not been included into the reflection process. While the Enlightenment unfolded and established its way of thinking, we lost sight of the fact that we, humans, not only have a natural propensity towards love, but that part of our being may also be comprised of hatred; or that we are not only thinking, but also feeling entities; that we not only strive for freedom, but also have a desire for education and cultivation. The negative aspects of us are being factored out of the equation. This is where classical ethics, the art of leading a good life, comes in. We have forgotten that. I think there is a chance, however, that we may enter into such a relationship with art – art being an activity that is an end in itself – that may help us. Maybe this is where we ought to begin.

AoA: The art of leading a good life is a lovely cue. Do we want to see more of it again today?

Aris Kalaizis: If we want change, we need to bring about a different concept of what a human being is. Or we at least need to think about doing so. Maybe we are all too much concerned with the Enlightenment itself. Modernity, when looked at critically, was after all made by philosophers. It was perhaps the first time philosophers caused such fateful change. But maybe we need to depart from the notion that there is such a thing as an illumination. And that if we only engaged long enough with that illumination, human beings will be illuminated, too. Quite the opposite is the case. We ought to assume that we are nothing. We, human beings, are actually quite nothing at all. We are not even human beings. We are the outline of a human being. If we are to emerge as human beings in the course of our life, then by way of actions. More or less good actions. This is how we incrementally emerge as human beings or develop towards being human. Tied to this, is the realization that we aren’t really in possession of a wealth of understanding, but a wealth of stupidity. We command a wealth of stupidity and need to spend it fully in the course of our lives as though it were excess weight. Because we experience a number of things, because we make mistakes – and everything that goes along with it. If we did so, I think, we’d come a step closer towards individuality, which is a burden to most people. It isn’t just pleasant the whole way. Artists, or in my case painters, lust for this challenge. I lust for this challenge. But many people view the challenge of becoming an individual as burdensome or are afraid of undertaking it.

AoA: Indepdence, sef-assertation is an important foundation in this context. Looking back, how did you develop such an attitude? How did you become an artist?

Aris Kalaizis: I’ve been socialized in the GDR. It was clear to me – when I was about fourteen or fifteen – that I ought to think about what I wanted or what I actually desired. Becoming an artist was already in the cards at that age. But, like most teenagers of my generation, I wanted to be a rock star. Or a professional soccer player. But without being able to play the guitar, becoming a rock star isn’t really an evening filling project, and soccer didn’t turn out that well either. To make things worse, I was really bad in school, too, especially in art class. I wasn’t that great in the natural sciences either. Awful would overstate it, but with respect to art class I was definitely awful. I began drawing relatively late at the age of sixteen, but already had a couple of painter friends whom I admired. I remember taking the train to the neighboring town called Halle, in order to visit a Greek painter, upon my mother’s recommendation. After the Greek civil war, that painter had been brought to the Soviet controlled zone, just like my mother. He originally came from the same village in northern Greece. The experience was indescribable. The odor of turpentine. The atelier. The space. I was probably fascinated by the independence and self-sufficiency that this career offers, perhaps paralleled only with that of the writer. They have things in common. I probably wanted little dependency. Greatest possible independence. Although, however, our job isn’t as free as it may seem to many watching from the outside. Art history as well as the art market are certainly constraining forces. Nevertheless, I was determined to enter this career early on, because I’m a creature of the eye, because I get more out of things that I can apprehend with my bare eyes. What I see, possesses a greater veracity, as far as I’m concerned. If somebody tell is me this or that, but what he is saying doesn’t coincide with what I’m seeing, then I will reject what he is saying. I think I started doing that ever since my school days ended. In those days, the question of being became relevant to me. I probably evolved into that pictorial domain by way of playing with its possibilities and a pre-existing interest in music, by designing simple record covers and t-shirts. Until friends came along who had similar leanings towards surrealism or who wrote poetry or painted or produced illustrations. Thus this love for art gained momentum, became the most important thing and my life, and continues on until today. If, today, I’d discover something in it that I didn’t like, I’d stop. But there are few decisions I made that I wouldn’t repeat. Like, say, soccer. It was the greatest love of my life.

AoA: You’ve been quoted saying that once your work hung upon the walls like led, but now your paintings sell pretty well. Today, you are considered established. Have there been any doubts along the way?

Aris Kalaizis: Sure, there are always doubts. Especially, when you start being successful. That’s when you are particularly asked to revise and check our approach. Because success is inveigling. It keeps people from reconsidering and reflecting on things. Success actually sets the tracks, it separates the wheat from the chaff. Success is the time in which you need to set the course for the future. It isn’t a time to let go of the reigns. With respect to a painter, this mean that one makes sure not to repeat oneself, but that one tries to paint even better pictures that one ever thought possible. I prefer the path of the seeker over the certainty of one who believes to have found something and goes on to reproduce it.

AoA: There is doubt, on the one hand. And there is the sense of a crisis, on the other hand. Did you ever experience anything close to a creative crisis?

Aris Kalaizis: Certainly. It was in times of crisis that I actually went forward. Essentially, I paint in order to bring about crisis, because crisis is what propels me forward. I think those phases of uninterrupted work certainly have been nice, but they didn’t push me forward as much as those other phases did. It’s like a body that has contracted some sort of infection. That’s uncomfortable, the temperature rises, the body struggles with the virus and eventually shakes it off. In the aftermath, the body is stronger with respect to such contagion. When you interrupt your work and let the crisis run its full course, then you experience something similar to an infection. In my case, whenever I believe to have accomplished something, it’s important for me to distance myself from that accomplishment, to take a step back, and to take a break, in order to put things into perspective. It’s within that interval, in which the crisis happens. The crisis doesn’t just come along without reason. The more you are away from your work, the more you feel that you are not one with the universe. And even the things that you had painted previously, are revised, are looked at in a different light, and have been injured. And after your earliest work has become subject to this desire for revision, then you will go on to revise everything you have ever done and look at it again critically. This doesn’t happen after every painting, otherwise I couldn’t ever paint anything new. It takes place in larger cycles, I would say probably once a year.

AoA: You’ve also mentioned that you need a sense of emptiness, after you completed one painting and before you begin a new one. Is there any connection?

Aris Kalaizis: Yes, it indirectly has to do with it. Because you are still under the influence of the painting that you just finished. Everything is still ever so present. And I’d be lying, if I’d now continue seamlessly on into the next painting and thereby negate the feelings that I had with the one that I just finished. They exist, even though unconscious, within me. In that sense, the process of distancing myself from the old painting, is a sort of separation. I then don’t want to see that painting anymore. If it isn’t immediately sold, then it’s in fact still present, but I don’t want to look at it. Not because I don’t like it. But because the goal of emptiness consists in being as receptive as possible and as unaffected by anything that had been hitherto. I don’t want to tread on paths that I already have walked on.

AoA: Emptiness and filling up again. How does that happen? How should I imagine that?

Aris Kalaizis: One must first impose upon oneself a ban on productivity. Don’t produce anything. That doesn’t mean that I’m not working. It just means that I’m not working productively. I usually do pretty common, everyday stuff, during those periods. I don’t sit down in a library and wait. That would be stupid. But in the final analysis it’s indeed a kind of waiting, even though I carry on with my life in the course of it. I do not only feel the urgency to paint something that will perhaps survive me. I also feel the urgency to put a nail into the wall or to build something else or to destroy something. That’s possible, too. And that’s a way of creating distance. You mull over a couple of things in your mind and the new already is dawning, though far upon the horizon, it’s gradually dawning upon you. Or maybe not in your mind, but in your subconscious. That’s where a lot of things come from. And it’s always difficult to discover rational arguments for our own work in the realm of the irrational.

AoA: We’ve now learned various things related to your creative process. Could you perhaps describe how it exactly works? What role for instance does the model play?

Aris Kalaizis: Basically, building a model stems from my need to see something. I’m not, never have been, particularly great at sketching things. I’m not the kind of guy who will quickly, by way of a few lines, will give you the anatomy of a dog or a cat. What that means is that I always need something to look at. And by looking at it, I may study it and by doing so I’m able to act. By acknowledging that, I realized that I’m not a serial painter – even though I did have a brief postmodern phase between 1997 and 2001/2002. A painting that is planned long in advance is something that I’m more comfortable with. In doing so, I have always worked with photography. I also preferred photos over human models that simply are a source of anxiety and nervousness for me, too. If someone is present or not, may be irrelevant to many people. But even if only my wife is standing behind me, that would be terrible for me. I couldn’t do a single brush stroke. That’s also why I have screened these windows here. I don’t like to be observed while I work, and I don’t want to look outside while I’m painting. I want to be alone with the painting that I have in front of me, so that I may enter into that cosmos, so that I may work at the greatest height possible for me. But let me return to your question. Building a model was just something that worked best over the years. The more accurately I was able to work out the model, the more I was able to introduce corrections in order to make changes or to bring about the possibility of change. And we are talking about models that are built today, but may remain assembled for a few days or sometimes even weeks. This is, of course, a very comfortable situation, in order to review every possibility that you have and to correct any mistake that may have snuck into my design. But this has nothing to do with copying the model to the canvass, one-to-one. The model is the basis for a painting, nothing else. It’s a kind of backdrop, upon which each painting is based on. It’s about the power of forms that may work this or that way within any given painting. And I attempt at painting the picture, so that it creates – in my opinion – the highest degree of tension possible. So, on the one hand, you’ve got the model and then you have the constellation, in which the figures are introduced. But the framework must already be as clear and as abstract as possible, when it’s built. In the wintertime, I usually build models indoors; and during the summer, I go outside. I own a little piece of forest where many pictures have originated. In my opinion, indoors clear, abstract structures dominate, and outdoors natural things may gain prominence. Outdoors, I take the opposite approach. I take the wilderness of the background and construct clarity in front of it, perhaps less complicated entanglements. But there are not only paintings that are created in response to a model. There are paintings that are informed by all kinds of influences. In the end, none of these models, the constructed realities of models, are sufficient in order to deduce a painting from them. They are simply a means to an end, in order to get closer and in order to do things with this model that ultimately need to be decided at the easel. Otherwise, I would need to paint at all.

AoA: Is building a model a sort of prototypical approach?

Aris Kalaizis: For me, it’s a way of approaching something, that’s all. The model, as soon as the general situation is clear, usually is pretty quickly discarded. I then no longer need it and do not want it any more, this other truth, and begin realizing the painting. I can build as many lovely models as I wish, but if I’m not able to realize it convincingly on the canvass, then all the fuss is good for nothing. I’m primarily concerned with painting, with color and form, with realizing my vision in a convincing way. That’s what matters. That is way I dispose of the model as quickly as possible.

AoA: How much time do the individual steps consume, beginning with emptiness to conceptualizing, to building the model, to realizing the actual painting?

Aris Kalaizis: This, of course, varies frequently, but generally I’d say that I spend the same amount of time painting as I do preparing. With regard to my current project, this will certainly be the case. I will need about two to three months of preparation and the same amount of time realizing the painting. Hopefully. And whenever I complete a painting, I reenter the phase of distancing myself from it by doing pretty common tasks and other things. I read each day, for instance, but I don’t visit exhibitions, while I’m painting. That’s something I save for the time between projects.

AoA: Preparation occupies a lot of your time. We’ve learned quite a bit about the model as well as searching out appropriate locations. How important is support you get from friends and acquaintances in this context and which influence does that have on your work?

Aris Kalaizis: They are helpers. When, for instance, I was working on the painting »Making Sky«, I only had a vague idea of the spatial situation. I knew it needed to be a room with a broken-in ceiling, through which an angel may enter. The room needed to be large enough to house beautiful, large forms. You may consider yourself fortunate if you know somebody who is familiar with such locations in Leipzig and who could take a couple of pictures and make suggestions. Then you review those suggestions and hope to find something that works with regard to location, opening, the general layout of the place, and so on. So, if there is something that works well with what I’ve got in mind, I go and take a picture of the place myself, print it out, and hang it up above my bed. Everything else then follows from there. I occasionally stare at it apathetically – in the evenings before I go to bed. I don’t know what you could call it. I’m a bit hesitant to call it »cognition«. It’s a difficult process, and it’s difficult to find words for it. Something like a relationship develops gradually, and I attempt at shaping that which is in front of me. And then I fall asleep and when I wake up the next morning, thinking »exactly, the angel needs to stand on top of the table«, then this realization is binding, imperative. I then follow that initial notion. It all needs to be in my head. I used to makes notes. Today, I don’t make any notes, because I believe that I will not forget the important elements. If in the following morning, I need to search for the solution I had come up with the night before, then the solution wasn’t that great after all.

AoA: You mentioned helpers that influence your work to a certain degree. Are there any other influences? What about your forebears in the history of art?

Aris Kalaizis: It would be foolish to say, despite your better judgment, that you haven’t been influence by anything. It’s important, especially if you’re at the beginning. You must be allowed to raise yourself with the aid of those who already accomplished great things. You usually don’t notice until later on that the influence of those, who you tried to rise yourself up on, was too massive after all, so you needed to distance yourself from them again or took them down or whatever. But comparisons are absolutely productive and important. But it’s important not to let that closeness to other painters to become too overbearing. When you’re young, you perhaps have a vague premonition that you are something special, something more beautiful than others. At one point, you realize that it was an illusion. But by working continually, by hanging on, you gain experience. Only in doing so, you may be able to bring down a titan, if you’re lucky. But experience doesn’t come from conversations. It only comes from doing things.

AoA: So it’s all about experiential knowledge, not about factual knowledge?

Aris Kalaizis: Exactly. You grow from the paintings that you create. Each painting rests upon its predecessor. That’s the primal concatenation that ultimately represents every painting you ever made. It would be nonsense to pick out an individual painting and to say, »that’s how I did it«. Because you need to look at the broad picture, in order to be able to evaluate individual elements.

AoA: How does that blend with distancing yourself from your work after you’ve completed a picture?

Aris Kalaizis: Experience, from my perspective at least, always needs to be based on preceding events. I’m not saying that I’d like to leap from one ice floe to another. What I’m saying is that if it’s supposed to be a productive experience, it would be stupid to negate that which was, even if I’d maybe like to suppress it. It’s after all within me, unconsciously. And I, of course, consider them as a point of departure, as a basis, and I don’t ignore them, as some artists do these days. They paint like this one day and differently another day. That’s not what I got in mind.

AoA: What role does criticism take in your work? Do you admit criticism, even while the picture is just slowly emerging?

Aris Kalaizis: It depends somewhat on how the painting comes along. In the early stage of painting, I actually dislike people commenting on it. Consequently, I wait until about half of the painting is completed, when one may already anticipate which route the whole project is taking. But it’s often the case that I can’t separate those things. It’s in the nature of my occupation that it’s solitary work. It requires corrective action. For that reason, I frequently have visitors in my atelier. We then, of course, also take a look at the unfolding progress of what I’m currently working on. The visitor then will sense if I want to talk about it or not. I like intimate conversations. I greatly profit from the opportunity of discussing my work in private with one or two people. For me it’s important to have a daily routine. When I step in front of the easel and begin painting, I’m disciplined and do not allow being disturbed. I need the time, the hours, in order to get into the painting. In the evenings, I enjoy company. For me, it doesn’t matter if that’s a professor or a cabinetmaker. I have indeed received criticism from simpler minds that was worth considering and brought about action, too. Say, I have an electrician working in my atelier. He may take a look at what I’m painting and give me his remarks. Something baffling then occasionally happens, and that person sees something that I have overlooked, because I’m too close with the painting.

AoA: What do think about the role of art, today and in the future?

Aris Kalaizis: Let’s distinguish between looking at art and creating art. When you watch people pursuing an artistic activity – it doesn’t need to be painting, it could be pottery, – you’ll notice that they are totally immersed in what they are doing. The activity may lead to something that you will never achieve by just looking at things. But I fear there is also a negative development taking place currently with respect to that. People are not left to themselves anymore. They are sometimes even patronized. I often get agitated, when I visit exhibitions and I’m told what I’m supposed to think what some curator has come up with. When I’m coerced in using the audioguide that offers prefabricated interpretations, while exploring the exhibition. To cut it short, here, too, freedom is being constrained, instead of letting consciousness expand by itself and on its own accord. In doing things, people tend to make experiences that they wouldn’t have made otherwise. It would be, however, quite possible to make such experiences in a museum or in a gallery setting, if only there wouldn’t be this external mindset that obviously doesn’t trust people with thinking for themselves. This may have various reasons. I’m only noticing that people read less and less. Thus people are not experiencing dreamscapes. They don’t make connections, don’t construct things in their mind. They don’t undergo that creative process that weaves everything together. I’m constantly asked, »What is your view on this? What do you think about that?« But then I need to be resolute and say nothing, even though I might have the most inspiring interpretations or maybe in fact do. But I don’t want to impart them upon the world, because I don’t want anybody to think about my work in the same way as I do. That would be a dead thing. I want to learn about things that I haven’t considered with respect to my work.

AoA: This is why you do not give any interpretive commentary on your own work, right?

Aris Kalaizis: Yes. I act upon the premise that I do not have anything to say. My truth is that of the paintings and of creating paintings. That’s my sense of veracity and if something happens beyond that, then it makes me happy. But I will not step next to my paintings or even step in front of my paintings and give additional commentary. I vanish behind them. Because I’ve already opened the door a bit by creating the painting. Now, the ball is in the court of the beholder. It’s up to him or her to push open the door or to close it. That’s his or her responsibility. My responsibility extinguishes as soon as the painting is completed. And I prefer to vanish behind my paintings and not to give any further comment. And that’s what counts in art history. We don’t admire El Greco and Ribera and Velázquez, because they had great ideas, but because they produced great paintings. Their motifs and themes are derived from the bible – there’s nothing new about that. The intellectuality of their paintings consists in the way they have realized their subject – what kind of color and form and what sort of composition.

AoA: How do you perceive the business world or people from the business world, as an artist?

Aris Kalaizis: There are all kinds of people, of course. I’m invited by McKinsey once a year to Kitzbühel and meet Business-Leadership folks there on the board level, while they engage in all sorts of activities for three or four days. Naturally, I conduct seminars focused on painting. In the course of the visit, you exchange ideas and talk with each other. Like in everyday life, people vary greatly. You connect better some people than with others. One person responds well to art, another person doesn’t. Nevertheless, for the most part, exchanging ideas with those people was productive. But I think there should be much more exchange between art and business. Perhaps, some sort of deeper correspondence may help to avoid further damage of companies that got into trouble.

Because you can’t solve problems without creativity.

Info

Text by Thomas Koeplin.

The interview was conducted by Dirk Dobiéy and Thomas Koeplin on 24/07/2014.

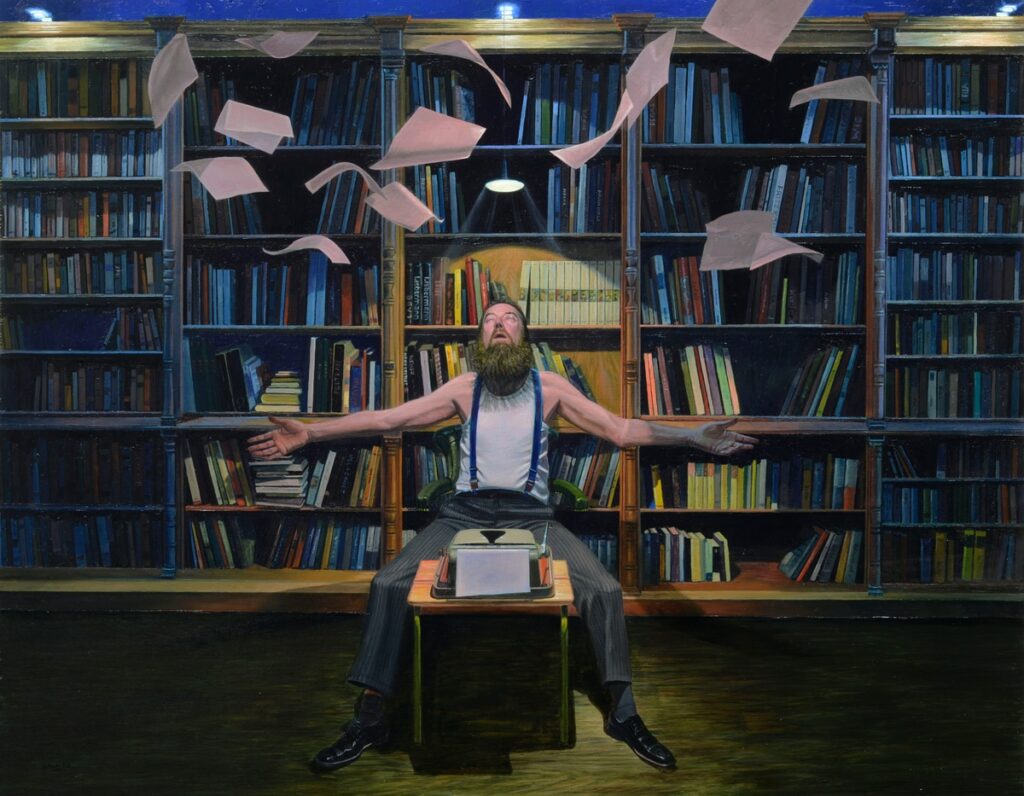

Image source: Aris Kalaizis.